I’ve spilled much ink, and darkened many pixels describing the community dimension of Cursor, but I’ve had relatively little to say about its publishing dimension, in particular as it relates to established writers and the traditional publishing infrastructure. I have mentioned that we would be doing some classic indie publishing, but that’s gotten a bit lost amidst all the rest.

So let me say here [well this is crossposted from The Literary Platform so I said it there too]: each community is also a publishing imprint, one that will publish one to two books a month. So, for Red Lemonade, the first community/imprint based on the Cursor platform, each of these books will be published digitally — both in the cloud, and as a download — and mechanically, as a limited edition and as a trade paperback original, this trade edition being distributed in the conventional manner by leading distributors around the world (details of authors, distributors, etc., to be announced at Book Expo America at a panel on rights and royalties y’all should check out if you’re going) and all editions being promoted with galleys, co-op, review copies, hustling, moxie, and my own brand of pimpin’ and hoin’.

Why bother, why continue to participate in this old system?

First off, Cursor is a community business, a writer-and-reader-driven business. To eschew the format and purchasing preferences of the vast majority of our community is to do them an enormous disservice. It is not our job to decide formats; it is the reader’s choice.

Second, my previous company Soft Skull derived a great deal of its success from the support of, let’s say, five hundred bookstore clerks, freelance book reviewers, sales reps, and librarians, people who are, yes, part of the disintegrating supply chain, but who are also part of the vibrant and ever more dynamic book culture ecosystem.

The best way to enable them to get the word about our books, about our community, about our writers published and unpublished, out to all the readers and writers they talk to is by participating: by having our books sold into their stores, by having our books reviewed by their conventional media that helps librarians, booksellers, and yes, even readers make purchasing decisions, by having the books visible in those places most highly trafficked by avid book readers and writers, by making books available to readers’ advisory librarians.

I admit, it freaks the investors out a wee bit, participating in this expensive and barely profitable part of the business. We’re not selling to the trade to make money, we’re selling to the trade because we owe it to the community. (Plus, we’ve other ways to make money.)

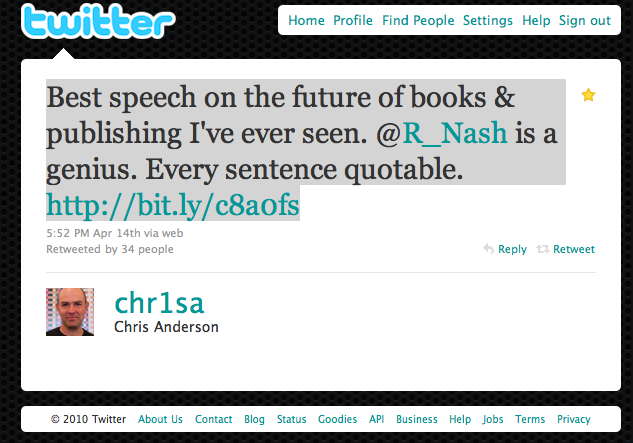

But we wouldn’t be Cursor if we didn’t tweak this. And the tweak is pretty radical. It’s not really a tweak at all, it’s a complete break with publishing norms. It already rather freaked out Jack McKeown, former head of adult trade at both HarperCollins and Simon & Schuster, and founder and former CEO of the Perseus Books Group when I hinted at it during the Digital Book World conference in January. When I discuss the details at Book Expo America at the end of this month, it’ll likely freak folks like Jack out even more.

No more life-of-the-copyright contracts.

Instead: three year contracts.

Yup, from a contract that locks you in till seventy years after you’re dead, to a three year contract. Renewable annually thereafter. Which means after three years you can walk. Or stay, but stick it to us for better royalties because there’s gonna be a movie. Or stay with us because with all the additional formats and revenue opportunities we’re creating above and beyond what any publisher has to offer, you’re making more money than ever before.

You see, most publishers have accepted they’re not going to make money publishing your book. They’re publishing your book and a bunch of other books like it so they can have exclusive rights over as much intellectual property as possible. Such that if, three or five or nine years down the road, you win the NBA, or the Orange, or there’s a movie, or an Oprah pick, your whole backlist starts to sell but they don’t have to pay you one single extra red percent in royalties.

That’s where their profits come from, from being able to NOT have to renegotiate royalties when your books start selling better than they expected.* That’s what freaked out Jack (sorry for singling you out, man, it’s just you were the one that saw the implications for the old business model and spoke up.)

My wife’s an intellectual property lawyer and deals all the time with negotiating licenses for intellectual property in fashion, cosmetics, software, design. She’s negotiated for or against DC Comics, Disney, Mark Ecko, Chanel, Michael Kors, J-Lo, the Elvis Presley and Muhammad Ali estates and so forth in creating apparel lines, fragrances, resorts. These transactions don’t involve 100 year licenses, or 20 year licenses. They’re 2, 3, 5 year licenses, the underlying philosophy being that you’re together in business to maximize the revenues from the intellectual property and if the underlying value increases, you’ll renegotiate when the license is up for renewal.

Authors deserve the same terms.

The publishing industry is in a state of turmoil. New sales channels are arising, new formats, new terms of sale.

Authors deserve the chance to renegotiate as the industry evolves.

The number of books published has increased forty-fold since 1990, the number of readers has remained broadly static.

Authors deserve to be actively connected with readers, not just be made available to readers.

OK, so I just slid from contracts and terms and rights and royalties to more general business issues. I’m cheating in my rhetoric. But in the broader sense, the authors we choose to publish know they are publishing with us because we serve them best, by actively connecting them with readers, not because of civil law penalties for breach of contract. And we know we must serve them better than anyone, else they’ll be out of here.

Are there any catches? Only this: given how tight, focused, loyal and progressive our communities/imprints will be, and given the ease with which an author can renegotiate any and all rights, we’re seeking a fairly broad basket of rights in the license. Not necessarily film, because agents get pretty emotional about film, and frankly book-to-film agents know what they’re doing and tend not to miss opportunities, but in audio, in English-language outside the US, in magazine republication, in translation, in those licensing channels, each of our imprints is going to be more active and visible than individual authors or agents or general-interest publishers are going to be. When an imprint is as focused as ours are, foreign publishers, audio publishers, magazines etc, know to come to our distinctive stable of writers.

Moreover, not only do you maximize your licensing revenue through our model, the more channels we can use to reach readers, the more efficiently we can get you in front of readers, and the more ways we can offer readers to connect with you. We collaborate with those entities licensing from us so as to, in the phrase used in the magazine business, so as to “surround the audience.”

There have been inflection points in the history of the production of culture where business norms change radically. Oftentimes the baby gets thrown out with the bathwater. We think we need to maintain selective publishing into book retailers, we think that’s the baby. But the old contract is the bathwater. Away with it. Join the baby shooting out of the bathtub with the rocket wings. We are your leg up in the world. We are your platform. And you can still fire us.

*I’m semi-exaggerating. For example, under the 1976 revision of U.S. copyright law, authors (and all other copyright holders) are allowed to terminate transfers of their copyrights to publishers after a set number of years, with different provisions for pre- and post-1978 works. The U.S. Congress made such provision “because of the unequal bargaining position of authors, resulting in part from the impossibility of determining a work’s value until it has been exploited.” However, you can expect it to cost a minimum of $10,000 right now in legal fees to perform all the very complex filings necessary to accomplish this. And I don’t know how many other countries have such escape clauses.